Sometimes at the end of day of work as the sun is beginning to set, I cross through the courtyard from my office and I step foot into this sanctuary and sit near the back of the pews. As I lean back and look around at the empty seats and the slowly dwindling light, I am always a bit taken aback by the silence. How could a room like this ever be empty and quiet? This is the place where we experience the celebrations and memorials as we cycle through the year, the joy of Shabbat, the introspection of the High Holy days, the dancing of Simchat Torah. These are the seats that have been filled with the “regulars”, but also the mourners, the learners, the fidgeting kids, and tired parents, with spiritual visitors and those who simply enter this space to experience that support and caring which fills this room. As I look around, I can’t help but bring to mind these holy moments in the life of this community.

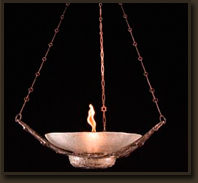

Yet while the silence that I find in this empty sanctuary is often a surprise, I also always notice how it is never fully dark. Even in an empty sanctuary there is always the ner tamid, the eternal light glowing dimly above the ark. Through the silent times and through all of the movement and change in our lives and the life of this community, the ner tamid remains, kind of like a silent friend who is always there delicately and calmly guiding us through it all. Now I do remember as a kid being mystified by the entire concept of this light, since while I understood the symbol, I simply couldn’t understand how they could make this special holy light bulb that never ever needed changing and wondered how we could get one for our bathroom! Of course I do now know that there is a plain old bulb in there that does need to be taken out on a regular basis, but the symbol behind the physics is still powerful. When we face east towards the ark, we face toward the Torah, towards the traditions and the story of our people. But we also always face the ner tamid, the eternal light, the continuing presence which has shined its light through all the winding road of our history and through the journey of our own lives. Whether the seats are filled, or the room is nearly empty, this faint light, allows us to see each other.

As we make our way through the story of Exodus this week, we are reminded of the powerful ways that light has kept our lives and community strong. This week, we encounter the final of the ten plagues, locusts, darkness and the death of the first born. Each of these plagues works to motivate Pharaoh to let the Israelites free, and even as his heart is hardened through each plague, Pharaoh must nevertheless watch his people suffer through each of them. Yet it is the darkness that really takes hold of the Egyptians, and it is what eventually leads up to the final and most devastating of the plagues, the death of the first born. This darkness according to our text is not just a lack of light, but a purely overwhelming darkness, a physical, spiritual and emotional darkness which takes hold of the Egyptians like no other kind of suffering.

This was a thick darkness, a darkness that could be touched. In this darkness, as we read “people could not see one another, and for three days no one could get up from where they were”, but that also somehow “all of the Israelites enjoyed light in their dwellings” (Exodus 10:23). Our tradition teaches us that the Egyptians were not just experiencing physical darkness, but the deepest of spiritual darkness–the darkness of depression or being separated from their people, and the darkness of communal pain. Some have said that in these short three days they realized the true horror of what they had been going through with the plagues, or even that they had begun to recognize the ways that their lives depended on the enslavement of others. In this thickest of darkness, the Egyptians could not move, they lost track of time and place and they, those people made strong under the rule of Pharaoh, felt all alone.

Rashi, the great Torah commentator while not silent about the other plagues asks the reason only for the darkness, “Why did God bring darkness upon them?” This is a thick darkness that confuses all of the the other senses and makes human interaction, and even worse for Rashi, teshuva, repentance, impossible. Without the ability to get up, without the ability to see or hear one another–there is no longer the possibility for relationship and community, and this from the viewpoint of a Jew is an unbearable kind of suffering. As the commentaries hint at, the Egyptians may have been sitting in their houses, unable to not only get up, but also not knowing whether there was anyone left in the world at all. This was a darkness of solitude, and with no where else to turn they and their people started to fall apart.

Of course we know that each cycle of day and night always includes darkness, and it is no coincidence that it is during the night when that we most often sleep–shutting our eyes to the world around us, and unconsciously delving within to our own thoughts and dreams. The Talmud tells us that sleep is 1/60th of death, that it is a time when our physical bodies and our spiritual selves shut down. But the Talmud also tells us what happens when we wake up and see that first morning light. Birchot HaShachar, the morning prayers are recited at dawn. And how do we know when dawn is? Not when the sun rises, but according to the Talmud, when a person can recognize the face of a haver, a friend (Talmud Brachot 9b). Only when we can see other people and recognize them for the ways they are connected to us, does the darkness begin to fade away. And only then can we offer blessings.

Martin Buber, the great Jewish philosopher expanded on this power of relationship through his well known concept of I-Thou. For Buber, he believed that we spend our lives experiencing much of life through two kinds of relationships, I-it and and I-Thou. I-It relationships are the most common, and are primarily functional–when we see and experience our relationships with others only by what they can do for us. We don’t know their personal stories, their inner lives, or what they care about or believe in. In a sense, we often quite purposely are kept in the dark about their inner lives, so our relationship can never move beyond the outward meeting. Whether we like it or not often see others in this way, people we pass by on the street, a supermarket checker, sometimes even neighbors and people we see on a regular basis become these I-it relationships. And we too are the its, as customer, clients, voters.

But the I thou relationships…these are the relationships that we are searching for, these are the relationships of meaningful interaction where both the outer and inner world of the individual comes together as we experience their essential nature. These kinds of relationships are not necessarily limited only to the people we love or care about, but anyone we meet, on the street, sitting next to us on the plane, or standing around the light of the Shabbat candles can be brought into this kind of holy relationship. It simply involves the deepest of listening, and clearest of vision and the knowledge that inside each person we encounter in the world is a story that we want to be a part of. Buber says it well: “All real living is meeting.” The ultimate goal of Jewish community, of any community should be to create a space where this kind of relationship and experience of connecting is both easy and accessible. When a person walks into this holy space, they should never feel anonymous or unknown. Each one of us should feel as if our story, our way of seeing the world matters and can add strength to our relationships with others and to the community. The nametags are a good start, but they are just the beginning.

In our community, as in very Jewish community, as the darkness settles on the world, we gather together for Shabbat to bless the joys of life, to take a moment to let go of the challenges, and to above all recognize each other. In the midst of the darkness, we light the Shabbat candles and gather the light reflected on each others faces. And then guided by this light, we wish each other a Good Shabbos as we make our way into the experience of Shabbat. As it says in the Torah, “and the Israelites enjoyed light in their dwellings” as the darkness descended on Egypt, we too continue to enjoy light through all the joys and the suffering taking place around us. The simple greeting of Shabbat Peace is a recognition of relationships and a reminder to the person whom we greet and to ourselves that we need each other, and that we are a community of individuals, waiting and needing to connect and bring light to each other’s lives.

Now after the plague of darkness, and the final plague of death of the first born, Pharaoh finally relents and lets the people go. Moses says that they all must go, people and animals, and then says that they “will not know with what they will worship God until they arrive there”(Exodus 10:22). For Moses and the Israelites their future is not set in stone, and they have only begun their journey towards freedom. They do not know what they will see in their journey and they don’t even know how they will makes sense of their ever changing reality. Their path will be a winding one, with mountains of communal celebration and joy, and valleys of individual suffering and pain–each moment, each turn only bringing them to another chapter in the the unfolding of their story. But this is a journey that they need to be on together, the entire community needs each other if they are to reach the promised land. And each and every member of that community is part of the light that will guide them there. In our community, we need each other as we wander through the wilderness together, and as long as we take the time to gather the light, our journey will also be our destination.