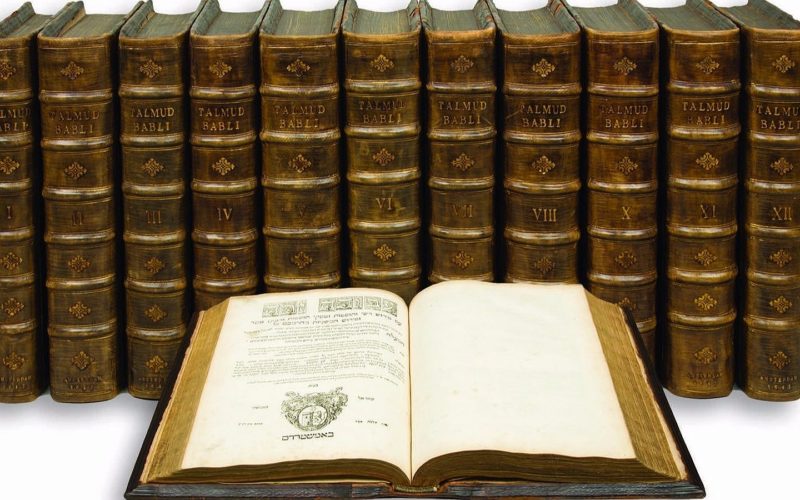

On a warm summer day a little over 7 years ago I started a habit. While I wish I could say I started daily training for a triathlon, or took on the challenge of fulfilling my lifelong dream to become fluent in Klingon, what I did was something that at least on the surface was much more mundane. Along with hundreds of thousands of other people around the world I began the daily study of a page of Talmud called daf yomi. I made my way through page after page, through the stories, the laws, the arguments and the questions. Sometimes I studied with others, or often alone, as I journeyed through the texts, enjoying and often being challenged by what I encountered.

This was a deeply spiritual exercise in so many ways, necessitating the commitment and focus of a meditation practice, but also the intellectual rigor of a university class. As the core text of the Judaism that we live and practice, I was fascinated by the conversations and found joy in discovering the roots of so much of what we do. Through my Talmud study, I read about why we light two (and not three or seven) Shabbat candles, and why we eat certain traditional foods, or say certain prayers. While I can’t say every page was interesting, looked at as a whole, it was a beautiful journey. Yet in the end, life, work and the good old stand by of an excuse–kids got in the way, and I only made it to about a year and a half. But tomorrow, I will attempt to start this process again.

The idea of Jews all over the world studying the same page of Talmud each day, is actually only a century old. At the World Congress for Agudat Yisrael in 1920, Rabbi Meir Shapiro, who was then the Rabbi of Sanok, Poland proposed the idea and it was passed. Before this time, Jews only were studying some parts of the Talmud, the most useful and most interesting tractates, and some sections were rarely studies. Most importantly though, Rabbi Shapiro saw the program as a way to unify the Jewish people. As he explained to the Congress delegates:

What a great thing! A Jew travels by boat and takes gemara Brachot Under his arm. He travels for 15 days from Eretz Yisrael to America, and each day he learns the daf. When he arrives in America, he enters a beis medrash in New York and finds Jews learning the very same daf that he studied on that day, and he gladly joins them. Another Jew leaves the States and travels to Brazil or Japan, and he first goes to the beis medrash, where he finds everyone learning the same daf that he himself learned that day. Could there be greater unity of hearts than this?

A page a day! This would not be too insurmountable a task with say, the Torah, the Book of Kings, or maybe Harry Potter. Yet, the Talmud, is not always as easy to deal with. While there are often fascinating arguments and wonderfully revealing stories and conversations that are recorded, there are also many dreadfully boring halachic arguments–back and forths about the minutiae of some archaic law, or arguments that are so complicated that they are laid out like calculus with words. There are uncomfortable exchanges about the roles of women in society, or laughably scientifically outdated statements, and sometimes even ideas that there is no way to see as anything but racist. It is an incredible mix of everything and anything, truly a work of unparalleled gems, and sometimes unbelievable drudgery.

As part of my rabbinical studies, I did study in detail some of the important sections of the Talmud. Both during my time studying at RRC in Philadelphia and also at Yeshiva in Jerusalem, we looked at some key sections of the Talmud–but this was no page a day. During my year in Israel while studying at Pardes, and Egalitarian Yeshiva in Jerusalem, we took our time covering, if I remember correctly, about ten pages of Talmud over the course of the academic year. We focused on the fascinating conversations and laws stemming from a simple question about Shabbat candles in Tractate Shabbat. I definitely enjoyed the pace, and taking our time to study this small part of the text allowed us to learn the vocabulary, and Talmudic ideas, but also left plenty of time to get off on endless tangents. We had conversations about candles, of course, which led to enlightening conversations about politics, gender, theology, Jewish identity, and one oddly heated argument about doorbells. Just like the rabbis of the Talmud would have wanted.

To say the Talmud has a structure, is somewhat of a strange statement. Yes there are sections, 63 tractates or sections divided by subject–from holidays to specific laws, put into six larger orders. Yet, to say that these sections necessarily hold texts that stick to their subject matter is far from true. One moment, you are studying one idea, and then a rabbi comes in and asks a question or tells a story (or in a not entirely rare moment, a joke or my favorite, wonderfully lighthearted insult), and then we are on to an entirely different topic that well, seemingly has nothing to do with anything. It is a truly incredible mix of structure, and the most free flowing conversations and arguments, with endless tangents and winding roads, and more than its share of dead ends. Yet, in the end, no topic is left uncovered. Some questions are answered, but very purposefully, some are not–the meaning coming from the conversations rather than the outcome

And what is the point of this strange structure? On a practical level we could argue that it was simply the reality of trying to record too many complicated ideas from a group of opinionated Jews, and there is bound to a little bit of rambling. Yet on a deeper level, the Talmud is telling us something very important about life. Everything is connected. Faith, identity, food, love, history, work, swimming, weather, sex, justice, prayers, women, men, gender, mathematics, the intricate details of a Hebrew letter and the deepest questions of human interactions. It is all a shimmering web of connection and mystery. These creators of Jewish life as we know it wanted us to see these connections in everything, to know in the deepest possible way that Judaism is not just about believing in a God, or connecting with our past, but it is about finding holiness in all parts of life, and questions in everything we do. If everything is connected and worth examining in detail the way the Talmudic rabbis do, then everyone word, every experience and truly every moment is a blessing, every exercise deserving of examination, and every experience an adventure waiting to be had.

Yet, beyond the text itself, I want to bring us back to the Daf Yomi, the process of studying a page of Talmud a day. This is not an easy task, and it involves a level of commitment that is actually very similar to any other healthy habit, like going to the gym or meditation. Each day, no matter what the weather, no matter what is happening in your life, you open the Talmud, and join the ancient rabbis for a few minutes. Like a workout, sometimes you might truly enjoy the process and walk away with a smile, and sometimes you may be happy to have the whole thing over with. As I mentioned, my first attempt to do Daf Yomi lasted only about a year and a half. I know that even without such a busy life, opening the Talmud each day was a big task.

The author Ilana Kurshan, who wrote a wonderful book about her journey into Daf Yomi called If All Seas Were Ink, puts it well when she writes:

A commitment to learning daf yomi is sort of like a marriage — you’re in a relationship for the long haul, even if most days there are no passionate sparks. Sometimes it’s hard to find anything meaningful or relevant on the page, but perhaps it helps to imagine those pages as the context for the more exciting material that will follow a few days later. Without the context, you cannot fully appreciate that fabulous story about the man who mistakes his wife for a prostitute, or the unicorns that could not fit into Noah’s ark. On pages where the topics seems less interesting, it sometimes it helps to pay attention not just to what the rabbis are saying, but to how they transition from one subject to the next. To learn daf yomi, you have to allow yourself to be carried along for the ride — and while it’s almost never smooth sailing, some days are certainly bumpier than others.

And this process of Daf Yomi, of pushing forward through the joys and challenges of the text, and the joys and challenges of life, is something I have been thinking of as I prepare to start this process again tomorrow. Our world is in a very different place than it was seven years ago, and it is not just our own lives that might be different. The political situation in so many countries has changed, the environmental crisis is wreaking havoc on the weather every day, and as I have mentioned before, I am having trouble keeping the hope that we can hold it all together and survive the next few hundred years.

And now to add to the challenges, we have the growing threat of anti Semitism. The recent attacks in New York and New Jersey are the most recent examples, shocking and horrifying incidents which force us all to realize that we are not quite as safe as we once thought. Those horrible ideas, those sick lies and beliefs that we might have thought were buried in the aftermath of the Holocaust are back. They are fueled by conspiracy theories, the dirty ocean of social media, and a US president that openly supports white nationalists and racist ideas. It is both unbelievable, and unfortunately, entirely expected.

And this is where we once again start Daf Yomi. Opening a page of Talmud, and entering the world of the rabbis is not only an act of study, but a spiritual practice, and a powerful and quiet act of resistance. Each day, we will continue to move forward in the text and in life, and will keep the connection with all of the other Jews who are studying along with us. We will move past the challenges, move ahead of the difficulties we find, and be guided not necessarily by answers but by questions.

This was clearly the feeling at the large Siyum HaShas gathering in New Jersey last week where thousands of Jews gathered to celebrate the completion of Daf Yomi cycle. The situation in the world, and the recent anti-Semitic attacks were on people’s minds, but, and this is the point, it was not the focus. A recent NY Times article put it well:

On a windy and biting cold day, the gathering offered a chance to affirm their faith in the face of those terrible acts. Some believed the event contained echoes of Jews who were held in ghettos or concentration camps during the Holocaust and resisted their persecutors by saying clandestine prayers, teaching their children the Torah or furtively blowing a ram’s horn on Rosh Hashana.

“You can’t compare it completely, but we’re showing that we’re not going to allow these attacks to change our course, change our language, change our clothing, change our God,” said Daniel Retter, an immigration lawyer whose parents escaped Austria under the Nazis and who participated in the Talmudic study with a dozen other members of his synagogue in the Bronx.

“The Talmud has gone through the Crusades, the pogroms, the Holocaust and too many atrocities to name, but the Talmud and the Jewish people have persevered and maintained our roots, and will continue to grow,”…

Yet, the Jewish Forward, saw things a bit differently:

But to the insider, the reality [of the event] was very different. In a four-hour long program, between a dozen speakers, the violence that this community now faces daily was barely mentioned.

It’s surprising, right? Just four days after five Jews were stabbed with a machete, and a few weeks after two Jews were murdered in a kosher supermarket in Jersey City, with hundreds of anti-Semitic incidents against visibly Orthodox Jews over the past year, you’d think that at a gathering of 90,000, it would be central.

It was not. Because rather than an act of defiance, the Siyum Hashas was entirely apolitical — it was no demonstration, no march, no rally. And it was an encapsulation of the fact that Jewish practice in the face of adversity is nothing new for us.

The event symbolized how much these attacks fit into the narrative that frum Jews tell of our heritage.

It’s this that the media has struggled to comprehend in its coverage of rising anti-Semitism against Orthodox Jews: Our understanding of our suffering has always had, first and foremost, spiritual significance. In every generation, they rise up against us, the Haggadah tells us. Traditional Jews take that literally.

Thus, during the Siyum Hashas, two of the leading rabbis of the Agudath Israel, Rabbi Malkiel Kotler and Rabbi Shmuel Kamenetsky did not allude to anti-Semitism, the ongoing threats, or the anxiety that many participants may feel. The Novominsker Rebbe, Rabbi Yaakov Perlow, mentioned it in brief passing. Throughout, their topic was singular: The importance of study, its centrality to our lives. They emphasized the importance of consistency, of aspiration — of not letting failure drag one down.

Tomorrow morning, I will open my Talmud and begin to study once again. I will join not only the thousands of others doing the same, but also through this process will in a very real way, become part of the story itself, joining the ancient Talmudic rabbis at the table to learn along with them. I will try, and I may again fail, to keep it up each and every day for the next seven years, but I will take it on as an exercise in commitment to my heritage, as a daily meditation, and especially now as an act of resistance against a very complicated world.

I can take comfort in the solace of the conversations of the Talmud, take a moment of pause from the pain and challenges that we see around us. As Talmud’s Rabbi Yeshoshua ben Levi says: “one who is walking along the way without a companion and is afraid, should engage in Torah study.” It is not always easy, but study, however you understand the term, guides us forward with intention, knowing that no matter what happens in our lives and in the world, there is always one more page to go.

Interested in beginning Daf Yomi study?

I hope you will join me and others from the Dorshei Emet community as we begin this journey together. We will look at the texts from a liberal, egalitarian and modern perspective, delving into the traditions but also making connections with contemporary issues, values and perspectives. Daf yomi study is for everyone, whether you are religious, secular, or just beginning the path of learning.

Join our Facebook group to learn along with the community:

https://www.facebook.com/groups/895018877567732/

Looking forward to learning along with you!