While this week we mark the final parsha of the book of Genesis, the powerful concluding chapters of the story of Joseph and his brothers, it is also an important time on our calendar–albeit, the non-Jewish one. This of course is the Shabbat before Christmas. Many of us joke about the Jewish traditions we have on this day–movies, board games, Chinese food or skiing, and many Jewish families take these traditions so seriously that December 25th wouldn’t be the same without them.

My personal tradition growing up in Oregon was to start the morning with my family, having a cup of coffee and bagels at a local hotel. Then we would make our way to the Jewish owned bookstore–which was always open on Christmas–and which became an informal meeting place for all of the Jewish book lovers in town to gather. We would spend much of the day there, reading, relaxing and taking our time perusing the endless aisles of the store. And then yes, we would finish the day with a Chinese dinner. We didn’t have any tree, there were no presents, and Santa never visited our home. But there was no doubt about it, although I was a good Jewish kid, I always looked forward to December 25th with genuine excitement.

Recently, multiple books and documentary films have been published describing many of these odd Jewish Christmas traditions, especially the connection with Chinese food and Jews. One of the best was last year’s CBC documentary “A Very Jewish Christmas” about the deeper reasons why so many of the best Christmas songs were written by Jews. And of course, the documentary takes place in a Chinese restaurant.

Yet what is especially interesting, and why this holiday is worth mentioning today, is that there are some very real traditions about Jews and December 25th. These move far beyond any commandments about what to order from the Chinese menu, but describe in detail the laws and traditions about what Jews should and should not do on this day. Exploring these traditions can help us understand how we have evolved in our connection with people of other faiths, and also how we have managed to turn the most non-Jewish of holidays into a uniquely Jewish day.

As you might expect, Jews have always had an interesting relationship with this holiday. For much of Jewish history, the challenges between Christians and Jews made Christmas if nothing else, an uncomfortable experience which brought into the open the minority status of Jews in society. For Jews in certain countries, Christmas primarily was a day to fear,

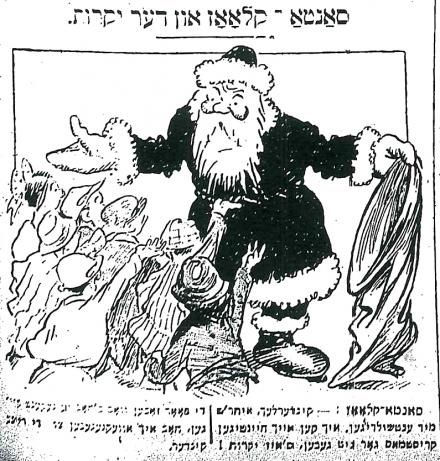

While we might think that the Jewish name for Christmas is the day of Chinese food and movies, there is a much more ancient source outlining the meaning of this day. Christmas was called by many Ashkenazi communities since the Middle Ages the somewhat mysterious name, Nittle Nacht. There are many possible sources of this title. The most common explanation is straightforward; the term nittel originates from the Latin Natale Domini, “Nativity of the Lord”. Yet, interestingly, when spelled in Hebrew, the words become a bit more derogatory, the “Night of the Hanged One” (nittel from talui “to hang”), or in a few slightly more complicated etymological word plays– the night in which Jesus’ life was taken from him, leil netilato min ha-‘olam, or the most technical, Nolad Yeshu Tet L’tevet, meaning, “Jesus was born on the ninth of Tevet.”

Even though this day has absolutely nothing to do with Judaism per se, Christmas of course had a very real effect on Jews and Jewish history. Because of the person that this day celebrates, one could argue we had thousands of years of oppression, inquisitions, the roots of a specifically deadly form of anti Semitism, pogroms, and much worse. With this truth, while we would not expect the Jews to be sitting around their tables with a kosher birthday cake for Jesus, being Jews, we of course had to have rules about what we could and could not do on this holy day of the Christians. And in the end, these rules led not to only prohibitions, but also a very real way that we were invited to celebrate, even as we were specifically not celebrating, on Christmas.

The main tradition, the most well known, yet in some ways the most shocking, is to refrain from Torah study and Jewish learning. The first source of this being Mekor Chayyim, the commentary of the Ashkenazi Rabbi R. Yair Chayyim Bakhrakh (1639-1702) which mentions specifically that Torah study should be prohibited on Christmas eve. From this and other sources it was clear that this was not an isolated practice.

No Torah study? This from a religious Jew?

It might come as a surprise to say that there is any day where one should not study Torah, since this is one of the core mitzvot of Jewish life. This act is considered one of the most holy Jewish practices, a way of exploring the truths of the world, of cleaving to God, and one of the most enjoyable acts that a person can do. So to create a tradition that there is a day when this should not be done necessitates some good explanations.

One common reason given is that one should not study Torah as a sign of mourning. As with Tisha B’Av, the day when we mourn the destruction of the Temple, we would then mourn to remember all the tragedies, all of the blood that has been spilled over the generations in the name of Jesus and Christians.

There is also a mystical view to the prohibition on studying Torah on Nittel Night which says that Torah study and learning brings positive powers to the world, and that it was believed by some to be inappropriate to do this on a day which some considered a time of idolatry, a celebration of a non-Jewish faith, and at one time, also a day pogroms and anti-Jewish violence. There was a concern that this Torah study could somehow honor or provide merit for the soul of Jesus, which was not desired. Or, on the most practical level, since Jews found so much joy from Torah study, they did not want to give Christians the wrong impression, to be seen studying on a day that so much of their world saw as a day to honor Jesus.

There were even some Hasidic rebbes who said that everyone should refrain from sleep on Christmas eve, just in case you might dream of Torah study. (Oddly enough, there is another tradition of doing exactly that, of sleeping on Christmas, to prepare for the study to begin again at midnight). This rule to not study Torah was meant to be taken so seriously, that there was a Chassidic legend that said that wild dogs would visit those who those who “violated” the rule and studied Torah on Nittel Nacht (Bnei Yissaschar, Regel Yeshara, 10).

Or there is the following legend told about R. Jonathan Eibeschütz (1690-1764), an eighteenth-century Rabbi, who was asked about this curious traditions of refraining from study:

[Rabbi Yitzchak Meir Rotenberg Alter of Ger] recounted that once a priest asked the holy Gaon, rabbi of all the diaspora, R. Jonathan Eibeschütz of blessed memory, “Do you Jews have a time when you do not study Torah, and your sages wrote that the world stands on the Torah, and if so, on what does the world stand in those hours.” And Rabbi Jonathan Eibeschütz answered him, that the custom of Israel is Torah. And the fact that Torah is not studied, is Torah, and the world exists on that. (Jacob Emden,Sefer hit’abkut, Lemberg, 1877, p. 59a.)

Now, these being Jews, even with such a strange custom as this, there was disagreement to how not-studying-Torah was practiced! Some said that one should not study Torah until midnight, others said until the morning. Others had that habit of sleeping in the early evening, and then waking up at midnight to study. In some Hasidic communities today, people gather in the yeshiva on Christmas eve as midnight is approaching with their Talmuds in hand, waiting for the stroke of midnight when a community member or the rebbe hits the lectern, signaling that study can begin again.

But what was as important as the prohibitions, was also what people did instead. And this is where things get interesting.

Historically, these first traditions arose from the obvious need to fill the time which one was not studying Torah. If you were a religious Jew in the shtetl without Netflix or a good movie theatre nearby, you had to do something worthwhile instead.

Torah scholars we were told would use the night to play cards, and others including many great rabbis, were known to play chess. There are some later texts which speak about, clearly with a bit of humor, a tradition of ripping toilet paper to use on Shabbat for the rest of the year. This practice has sadly fallen out of use, because now you can by shomer shabbat ready pre-ripped toilet paper at the local supermarkets.

Other popular activities for the Christmas Eve included a wonderfully secular mix of common activities, including: spending the night balancing your checkbook or managing one’s finances, working on communal projects, reading secular books, learning a new language, or sewing. And if you had some time left after all of these exciting tasks, you should make sure to eat some garlic, since this was thought to ward off demons and any other bad vibes that might be floating around on this problematic day.

It is important to note that many of these traditions were found primarily in Hasidic communities, and most Jews outside of these communities never accepted any of these practices. While many Hasidic Jews still follow those traditions, many strongly oppose them. In fact, there are some well known rabbinic authorities who strongly oppose Nittel Nacht, calling it a waste of precious Torah study time. Though then some say that observing this custom, or any custom, is inherently like studying Torah, and therefore only good! Outside of Ashkenazi communities in the Sephardic world, there is very little knowledge of Nittle Nacht, since Jews in these countries didn’t have a similar fear of oppression. In the end, beyond all of this back and forth, there are some halachic authorities who simply say that we should follow these traditions, to use the technical term,”just because”.

I remember when I was the rabbi for the progressive Jewish community of Warsaw, and I was excited to introduce for the first time a gathering for Jews on Christmas, since much to my disappointment, the tradition of Chinese food and movies had not taken hold in the country. Blending the wonderful North American Jewish traditions with a lighthearted take on Nittle Nacht, we organized an evening of movie watching, card games, music and fried perogies. (Not quite dim sum, but reasonable Chinese food was hard to come by in Poland.)

While we always advertised our programs, this one seemed to get more publicity than usual. There were multiple radio interviews, a good size article in an online event website, and quite a bit of word of mouth publicity. The interest in the program was most likely for practical reasons, that so many people felt left out in this very Catholic country and were excited to have an “alternative Christmas” celebration. Yet, I feel there was also a curiously about what the Jews, this small minority group which once an important and large part of Polish society did on day devoted to Christians. It was a fun time for all.

It is clear that all of these strange traditions could have only evolved from a time and place where the Christian and Jewish communities were not on best of terms; Nittle Nacht and the customs of the day evolved from a place of fear and misunderstanding about Christian traditions, not from a respectful connection between the communities or, even, dare I say, from a deep desire to play poker. In a world where we live peacefully among Christians, where we accept and welcome interfaith families and promote interfaith dialogue, these traditions may seem at best humourous, and at worst, dangerous.

Yet, to put a positive spin on the traditions of Nittle Nacht, we have to recognize what is happening on a deeper level with the evolution of these traditions, and what it says about how we Jews confront the realities of the world.

As the Jewish community no longer had fear from the Christians, and as Jews lived in a world of coexistence with and respect for other religions, the traditions continued for more practical reasons. Most stores, restaurants and places of entertainment were closed, nearly everyone was on vacation, and there simply was not much to do! Jews being practical minded and creative, turned Christmas, a day of which was once a painful reminder of our separateness and of suffering, into a day of relaxation and fun. While we would miss out on Torah for a day, we could have faith that we could catch up with friends and family, do some straightening up around the house, and play a few games of cards. Not bad for a non-Jewish holiday!

Whatever your Christmas traditions are, Chinese food, movies, seeing Christmas lights, or celebrating Christmas with non-Jewish family, it is clear that this is no longer a holiday to fear, physically, philosophically or otherwise. While the roots of Nittle Nacht clearly do very little to respect or honor the celebrations of our Christian neighbors, they also leave a place to enjoy the season for many of the same reasons that they do. As so much of the world shuts down, if we take one stream of our tradition seriously, then we are commanded to relax, spend time with friends and family, and simply enjoy this quiet time in the darkness of winter.

As Jews have always done, we took what was for us, a normal day, and turned it into something better. It may not be our religious holiday, or a celebration of our faith, but we can always use an excuse to have a celebration of life. So L’Chaim to life, and may we all have a Merry, Merry…Tuesday!