Shanah Tova! I am so happy to stand here once again with all of you as we welcome in a New Year. We have made it through another cycle of the seasons, and as we sit here today, the wandering paths of our life stories once again come together, guiding us forward into the year ahead. This has truly been a time of growth and changes, of communal celebrations, and of possibly some personal tragedies. I am sure that we have had experiences which have made us deeply proud, and also those which have filled us with regret. We have had moments of loving connection, and maybe even times of profound loneliness. And our world, our society has been confronted with some very real challenges, political upheaval, environmental crises, a fight for values and a growing sense of division that hasn’t been seen in generations. In so many ways, our world is so much more complicated than when we sat here a year ago.

But we sit here together today, ready to take on this new year with intention and clarity. The High Holidays invite us to begin this deeply personal process within the safety and comfort of this holy space and the familiar melodies and stories of the season. Sitting next to others in our community, we can know that no matter what we are searching for this year, what questions and needs we may have, we are not in this journey alone.

And an important part of the journey we are on is the search for truth, a stable resting spot of clarity, understanding and acceptance in our very busy lives. A place where the toughest questions we have about ourselves and our world are made more clear, and where we are on the path to living a life of purpose. This path is of course stated strongly in the name of our synagogue, Dorshei Emet. Emet, Truth. When you think about it, this name reminds us of a very powerful fact, that as Jews, as searchers we never reach the end of this time of exploration. We are constantly searching, learning and questioning, and hopefully never feeling fully settled–headed towards ultimate truth but never quite making it there. And this word, this idea, Emet, truth is what I would like to explore today in this new year.

Emet–Aleph, Mem, Tav, the beginning, middle and end of the Hebrew alphabet. This word encompasses the wholeness and the breadth of Judaism. It is found in multiple places in our liturgy. In the final words of the Shema, Adonai Eloheichem Emet, in the 13 attributes, and is mentioned endless times in the Torah and other Jewish texts. It is clear that truth is in a very real way is at the core of the ever flowing mystery of Jewish life.

עַל שְׁלשָׁה דְבָרִים הָעוֹלָם עוֹמֵד, עַל הַדִּין וְעַל הָאֱמֶת וְעַל הַשָּׁלוֹם

Rabban Shimon ben Gamaliel used to say: on three things does the world stand: On justice, on truth and on peace. -Pirkei Avot, 1:17

We know that when we are given three values, they each in a sense hold equal power. Removing one is similar to taking off one leg of a three legged table. A world with only justice and no peace, a world with no truth, is a world doomed to destruction.

Now on the one hand we have to make a distinction between the more philosophical idea of truth, the search for meaning and purpose, and the facts and information that determine the different ways that each individual perceives and interacts with the world. In Judaism, both of these ideas are in a constant dialogue with each other. Learning and questioning leads to even greater truth, and finding meaning and holding onto faith better equips us to know how to interact with the world. On a more practical level, in our lives, we have to always decide whether something we read, or what someone tells us is based in reality or whether it is an opinion or simply false or somewhere in between. As we all know, today with the internet, with fake news and powerful and manipulative technology this task has become more difficult than ever.

Let me share with you a story, and I warn you, it may shock and bother you:

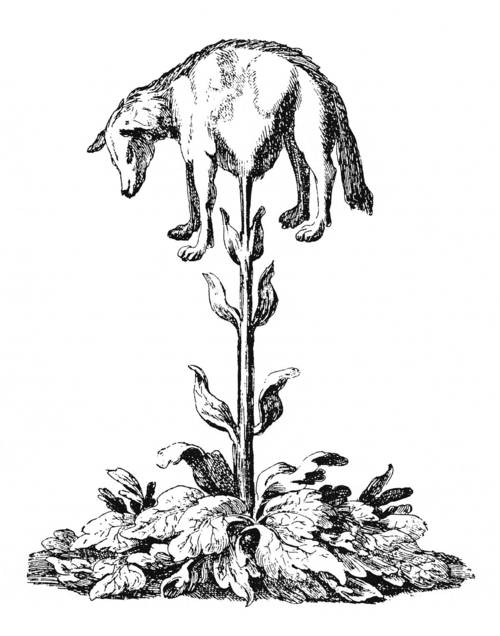

In the 13th century a text started spreading around Europe described in detail two amazing new plants that were found. The plants were discovered and examined by multiple explorers, and amazingly was first mentioned in our very own Jerusalem Talmud. The first of these plants produced little naked, newborn lambs inside its pods, and the other had a life-sized lamb, with blood, flesh and bones bones, attached by its belly button to a short plant stem. This stem was flexible, so the lamb could happily graze on the vegetation around it. Once all the vegetation was eaten up, or if the stem broke, the lamb would die. While there of course were no photographs of this amazing animal plant, there were very detailed drawings for those who didn’t believe. Google it when you get home, it is worth it.

Now you might want to think that this was the wacky talk spread around to some very gullible people, but this story lasted for over four centuries, and according to scholars, was almost universally accepted as fact until it was finally disproved.

And here’s the problem. No such text ever existed in the Jerusalem Talmud, and even more, a mere hint of common sense, and a basic understanding of botany and biology should tell us that no such thing could ever exist in real life. Ahh, you might say, such silliness is a product of a different time, that this is simply one of the more outrageous examples of a myth from of time where it was simply common to believe in such things.

Yet we know that false information and facts of different kinds are found just as readily in our times. Doctored photographs, manipulated information, gossip and lies are everywhere. You can look at the way that tobacco companies until this day hire “experts” to prove that cigarette smoking or now vaping is entirely safe. Global warming is not real, autism is caused by vaccines, the existence of certain political statements, college party photographs or inauguration crowds. A few well written Facebook posts, a bit of creative propaganda and the conversations can be turned, and reality can be entirely ignored. We can even curate a new story for our own lives based on what we post on the internet, choosing the best photos and sharing on those posts that fit on desired selves. Only in our current world can we even consider using the mess of a phrase invented in the past few years: “alternative facts”. Something has gone very wrong.

I often picture the rabbis who created the Talmud, the ultimate chat room of Jewish tradition as the original Dorshei Emet, pursers of truth. If you look at any Talmudic argument, its source is always stated clearly and in detail, and arguments which challenge these statements are recorded and are common. There are endless topics that are covered in the Talmud, some of which admittedly would not hold up to a more contemporary critical eye, such as some fascinating but odd discussions of magic and superstitions. (Don’t forget, by the way, that as a 13th century Jewish mystic said, “Jews should not believe in superstitions, but……still it is best to pay attention to them…”- Sefer Hasidim, Book of the Pious, 13th c. Germany.)

But either way, very little slips by without being examined in detail by the rabbis. A law or statement is not usually given and then ignored–it may lead the conversation on a truly mysterious tangent, or in the end make even less sense then when the conversation started, but the rabbis did not post, repost and walk away. A classic Talmudic argument is most similar to a mathematical equation, a complicated web of words, sources, questions and challenges, leading not necessarily to a final answer or proof, but above all is a process where as much as possible, every detail of every piece of information is covered and properly sourced.

The Jewish scholar Jacob Neusner wrote about the Talmudic process as a search for truth and order, but one that at its core is regulated and backed up at every stage of the journey: He wrote:

The presupposition of the Talmudic approach to life is that order is better than chaos, reflection than whim, decision than accident, mental activity and rationality than witlessness and force. The only admissible force is the power of fine logic, ever refined against the gross matter of daily living. The sole purpose is so to construct the discipline of everyday life and to pattern the relationships among people that all things are intelligible, well‑regulated, trustworthy and sanctified. (Neusner, Invitation to the Talmud: A Teaching Book, pg. 273)

The rabbis of the Talmud did what they could to ensure that in their ultimate goal to create a livable and powerful Jewish tradition, facts were clear and information was given in as honest a way as possible. In fact hidden in the Talmud itself is the important statement that “Truth is the seal of the Holy One, blessed be God. (Talmud Bavli, 55a)”

But this pursuit of truth is different today. When a world of information is literally at our fingertips, the notion of truth is much less clear. Today there are over 3 billion people who use the internet around the world, we produce over 2.5 billion gigabytes of data, do 4 billion Google searches, and watch 10 billion Youtube videos each day. (Tali Sharot, The Influential Mind, Pg. 13) With these numbers you can imagine that the entire meaning of truth, reality, facts and data are thrown in the air.

You might think that with more information, so much “data” easily accessible, we would be more informed and hopefully make better decisions, but as we all know, that is not necessarily the case. With all of these numbers, all this available information, we also know that we are not easily influenced by data or numbers. As people, we naturally don’t like to find our truths, to create our most strongly held values from facts, links or articles that are thrown at us. We evolved to get this information from lived experiences and relationships.

Tali Sharot says in her book The Influential Mind:

It is not that people are stupid; nor are we ridiculously stubborn. It is that the accessibility to lots of data, analytical tools and powerful computers is the product of the past few decades, while the brains we are attempting to influence are the product of millions of decades. As it turns out, while we adore data, the currency which our brains assess data and make decisions is very different from the currency many of us believe our brains should use. (Sharot, pg. 15)

Psychologists use the term confirmation bias to describe the way that so many of us look at information in the internet age. It is not a new idea, but it is something that is now amplified because of the way we access information today, where almost anything that I want to be true most likely is, as long as I know the right search terms to put in Google. If I want to proof that the moon landing never happened, or that global warming is a myth, of course I can find plenty of conspiracy theories to feed my needs. But I can also find proof if I need it to say that broccoli will kill me, that caffeine is healthy or caffeine is harmful, or that the life story of any celebrity, politician or leader is in fact one of many competing narratives. Some facts might take a bit more time to find, but without a doubt, alternative facts are very real. And we can’t forget that most search engines and social networking sites like Google and Facebook, run on algorithms, that actually are trained to spit back the information that we want to see, effectively closing us all off to anything that might challenge us too much. Whether we like it or not, we have been placed in safe little bubbles of comfortable truths, and it is getting harder and harder to get out.

In the internet age, I can say with certainty something that even the superstition prone rabbis of the Talmud would have been horrified by: Anything I want to be true, can be true. I can find a text, find a news story, take it out of context, cite it as proof, add it to a Facebook post and go on surfing. Quick and easy, no one gets hurt, and I can feel good that I have spread some useful information to others. Hey, and while I’m at it, why don’t I share an important fact I found, totally out of context for you! Current research estimates that at least 60 percent of news stories shared online have not even been read by the person sharing them. I actually do have the source for this, it is from a 2018 Columbia University study, but I just know that fact, because I actually didn’t read the whole article. (https://hal.inria.fr/hal-01281190)

This ease of finding anything we want has made us weaker. Not only does it make it more challenged to be challenged, but it also has dangerous consequences. We could argue that there is nothing harmful about an innocent bit of misinformation about a popstar or a favorite vegetable, but the outcome changes when it comes to political leaders, health or societal issues. The myths which have spread about climate change, autism or vaccines are dangerous, and that is only the beginning.

We need to know where our information comes from.

Our tradition tells us that citing our sources and knowing where information is found is not only a useful study skill, but is even a pathway to God. We are told that offering one’s source can bring ultimate salvation. From Pirkei Avot we are told “kol ha’omer davar b’shem omro, mevi geula l’olam” – whoever says something in the name of the one who said it [first], brings redemption to the world. (Chapter 6:6; quoted in the Talmud in tractate Hullin page 104b!!!) In the rabbinic mind, the search for truth, like the very identity of the Jewish people, can’t forget its roots.

Even in my work as a rabbi, I have experienced first hand the challenges of community building and searching for values where any truth is at hand. As a liberal rabbi, I am often cited so called facts about Jewish law or practice that clearly come from one viewpoint or one website, usually Orthodox, that leaves out any possibility of different viewpoints, an acceptance of different values, or even ignores the thousands of years of evolution of Jewish tradition and history. Sometimes, I now just simply respond, Judaism is much more than Chabad.org.

As a challenge to my interfaith work, I have been forwarded articles and videos about Muslims that are filled with myths and lies, but are given as facts because they come from one of many flashy right wing websites. Blatantly racist statements, shocking and hurtful stereotypes seem to fly freely in much of our Montreal Jewish community, but are considered acceptable because they have a nice link to go along with them.

I am given facts about Israel, and then in the same day given facts that tell a completely different viewpoint, and am told that being a true Zionist and lover of Israel means supporting only one political party or staying away from certain more left leaning pro-Israel organizations.

I have been forwarded links that explain to me, a 25 year vegan, that in fact eating meat is required for Jews, that is better for the environment, and that new studies show that in fact non-human animals do not have feelings or feel pain.

I have even caught myself at times citing Biblical texts or Jewish facts out of context, and realizing that without their surrounding stories or attributions they simply don’t hold their power.

I do want to tell you this–I am immensely proud of our community–the values that we hold as individuals and as a congregation, beyond our name, give us a constant reminder to be seekers of truth. We are activists, we are deep thinkers, and people who have no problem sticking up for our beliefs and asking the tough questions when they are needed.

Articles, posts, links and emails, it is hard to filter through it all–but to continue our constant search for truth, we have no choice but to take this task seriously. And the first step is to head back as the youngins say from the URL to the IRL–in real life. It is truly amazing what real people can do.

A few months ago I was on the way to a protest against bill 21 in Quebec City. One of the guests in the car was an imam, a young man, who in addition to his religious calling, was an engineer. In the course of the long drive north, stuck in the car with nowhere to run, we had quite a wide ranging conversation. We discussed Jewish and Muslim notions of God and faith, kashrut and animal rights, and even stepped off the deep end and got into a fascinating discussion of Israel, Palestinian identity and Zionism. I calmly explained to the imam why the land of Israel was so important to Jews as a refuge and spiritual home, about all of the places in the Torah and our liturgy where it is mentioned and what some of the differences are between right wing and liberal Zionism. He for his part, explained his connection with Muslim ritual and traditions, and helped me make sense of some aspects of Muslim belief and practice that I never fully understood or was misinformed about. There were plenty of smiles, some jokes and more than a few very tough questions. In another venue, this rabbi and imam could have decided that our differences were too great, and we could have walked our separate ways before any conversation even started. But stuck in the car, our bubbles proudly popped, we instead had a moment of deep learning, of deep encounter–and we both walked away with new insights brought on from a holy sharing of truths.

These encounters are in fact why I connect so much with interfaith work, and why I believe deep in my heart that it is one of the most important things we can do to strengthen contemporary Jewish community, and move us towards our search for truth and towards a greater sense of peace. I’ll tell you a little secret, that meeting with the imam in the car a few months ago was was not my first. I have been meeting with imams, priests and ministers even before I became a rabbi, and this is in part why I have remained so proud to be a Jew, and why I continue to love my role as rabbi.

Listen, we do well with other Jews, we share a story, a history, a common language and at least in some important ways a similar world view. You share an understanding of my faith and practice, and you get my jokes. We both like bagels. But dwelling comfortably in this place, we have to be careful of the growing echo chamber of ideas and beliefs which we then create. When I have delivered a sermon at a local church or siting in a Muslim prayer service and discussion in a mosque, I am forced to explain myself and my identity in new and challenging ways. “Why am I Jewish?” takes on a whole new power when explaining it to someone who is not. I will of course continue to give my heart and soul to this community and to do all that I can to work for the good of the Jewish people, and it is undeniable and obvious that my Jewish identity is nourished and strengthened by participation in Jewish community, but it is also inspired and beautifully given life by sharing it with others.

This year in our community as some of you know, we are hoping to enact our new policy which allows us as a community to learn how to have difficult conversations as we discuss issues of value to the Jewish community. After some of the challenging situations brought up over the past few years, we are committed to bringing in speakers who will both educate us, and hopefully also bother us. Israel, and faith, Zionism and Palestinians, liberal and conservative, myths and truths. This is the year to open up our hearts and minds to new perspectives, and in the process learn as a community how to truly listen and learn from those who are most different than us. This kind of experience is the most Jewish way to learn, and beyond the topics that will be covered, it can hopefully also be a model that can help us explore the notion of truth and identity in other parts of our lives. It is not as easy as sitting in our pajamas conversing with the Googeler Rebbe, but its impact can last even longer.

This New Year, this celebration of Rosh Hashanah, new beginnings and the deepest acts reflection and repentance, invites us to examine the question of truth on every level. In the busy complicated world in which we live, the very notion of truth has been upended, and it has had a deep and powerful effect on the way we interact with each other and take care of our own lives. With the internet and endless information at our fingertips, with our society polarized into camps based on beliefs and values, we spend more time trying to prove we are right, instead of asking questions and listening to others. It is time to step back. Teshuva is a reminder to hold on to our own truths, and examine ourselves and our relationships in a clearer and more humble light, yet also be open to real and deeper experiences which bring us out of our bubbles and invite us to step into the uncomfortable reality of difference.

It is time to start making decisions, especially those that affect our health, our relationships, our community, and our environment not from Google searches and Facebook posts but from deeper acts of learning and searching for truth. Searching that can only come from the conversations found in community, from lived experiences and from always questioning the information that is thrown our way. While it is sad to say, we may need to trust less of what we read and what we hear, but even more, we need to begin to trust ourselves.

The questions we ask of ourselves at this time of year, do not have answers that are easily searchable:

It demands that we ask ourselves: am I living a life of integrity, honesty, and wholeness aligned with what I know to be true?

Do I live according to my values, and am I in a constant search from where these values come from?

Am I open to listening with a renewed openness to others, and to learn from those people whom might have opinions and values that are different than mine?

As we sit here today, we need to look deep within, placing ourselves before the mystery of the universe, and look beyond what others tell us we are.

This time of teshuva demands the deepest listening.

As we head into this New Year, we need to remember that truth comes from questions and perspective and from conversations and encounters. We need to head back to the “truths” of deep learning, relationships, and good old fashioned research. This will lead to facts that can be trusted, and actions that can make real change. We need to gain strength from the unknown, and healing from the unanswered questions, and above all know that we have each other to share in this journey. As we help guide others through the mystery of existence, we end up guiding ourselves. Let’s all live up to the name, and no matter what else we do in this New Year, I hope we can all work to be Dorshei Emet, pursuers of truth.

Shanah Tova!